By HPO Composer-In-Residence Abigail Richardson-Schulte

Part 1. Discover the World of Franz Schubert

I am so excited to have Franz Schubert (1797-1828 – yes, he died at only 31 years of age) as the featured composer of our annual HPO Composer Festival. In his day, he was primarily known as a composer of vocal and piano works. However, his overall output was so much larger. In the decades after his death, other composers championed his works. Gradually the extent of his works and talent became known across the world. Here is a glimpse into Schubert’s world:

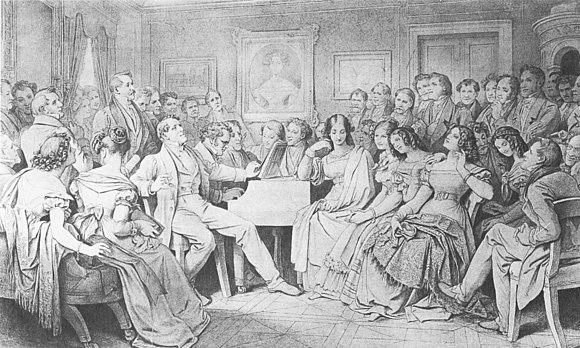

Schubertiades

As a teen, Schubert won a choir scholarship to study at the Stadtkonvikt, the Imperial Seminary. There, he made lifelong and remarkably dedicated friends who supported him in his career. They brought their own friends and everyone gathered at parties in Vienna to hear Schubert play his latest works. These gatherings called “Schubertiades” revolved entirely (or almost entirely) around his music. A few to over a few hundred people would come together to enjoy food, drink and even dancing, or they might be purely musical and move to a tavern or cafe afterwards. Schubert would perform his small scale piano pieces himself and team up with singers to perform his adored Lieder: songs for voice and piano.

Of the evenings, Schubert’s neighbour and friend Schwind recalled:

“There could be no happier existence. Each morning he composed something beautiful and each evening he found the most enthusiastic admirers. We gathered in his room – he played and sang to us – we were enthusiastic and afterwards we went to the tavern. We hadn’t a penny but were blissfully happy.”

REPERCUSSION AND REPUTATION

Schubertiades were unfortunately not always blissfully happy. The police broke up one of these parties, suspecting revolutionary activity after the French Revolution. They arrested Schubert and friends, and one went to trial and prison for over a year, followed by banishment from Vienna.

Even though these small, private gatherings sound incredible, the tradeoff was that Schubert was known as a “Hausmusik” composer rather than one for more prestigious one. Consequentially, this caused some not to take him seriously or value his more serious works.

Franz Schubert and Ludwig Van Beethoven

Franz Schubert was 27 years younger than Beethoven. He also grew up as a young musician in the city of Vienna where the great master lived and worked. Can you imagine? Beethoven’s life and works were a guide and a shadow to Schubert at all points in his life. Schubert only outlived Beethoven by a little more than 18 months and took over as Vienna’s major composer for that brief time. As a student, he played in performances of Beethoven’s first two symphonies. According to one biographer, Schubert sold a few books to get money to buy a ticket to see Beethoven’s opera Fideleo. As a freelance composer, sometimes Schubert had money and sometimes he didn’t.

Schubert was among the torch bearers at Beethoven’s funeral. On his deathbed, he requested to hear Beethoven’s String Quartet in C# minor, Op. 131. A string quartet played it to him at his bedside. The violinist of the quartet said “Schubert was sent into such transports of delight and enthusiasm and was so overcome that we all feared for him. The quartet was the last music he heard. The King of Harmony has sent the King of Song a friendly bidding to the crossing.”

MEETING BEETHOVEN

There are conflicting reports on whether Schubert actually met Beethoven. Considering their careers as the top two composers in Vienna at the time, it’s hard to imagine them not meeting. Then again, by the time Schubert was an adult, Beethoven was already suffering from deafness and was socially reclusive. In 1822, Schubert dedicated his “Eight Variations on a French Song” to Beethoven with “profound respect and admiration”. According to Beethoven’s friend Schindler, Schubert dropped by Beethoven’s apartment with the publisher to present it to him. Schindler said that shyness overcame Schubert and he lost his composure when Beethoven pointed out a mistake. Reportedly, Beethoven did appreciate his dedication and played through the piece numerous times.

Schindler claimed that Schubert never visited Beethoven again, though others say Schubert visited Beethoven about a week before Beethoven’s death in 1827. Apparently Beethoven knew little of Schubert’s music until Schindler showed him over 60 songs in Beethoven’s last days. The high quality of the compositions impressed Beethoven. He stated: “Truly, there is a divine spark in this Schubert.” Biographers on both sides point to both artists wishing they knew each other more. In a delirious conversation with his brother the night before he died, Schubert requested burial close to Beethoven. This did indeed happen. Even when Beethoven’s remains were moved in 1888, Schubert’s remains were moved alongside.

Franz Schubert’s legacy

When Schubert was alive, he was known for his piano works and his Lieder. He saw some success with chamber music, but struggled to gain recognition as a symphonic and opera composer. Italian opera was all the rage in Vienna, and opera companies were much more interested in Rossini than Schubert. His symphonies were read by a conservatory orchestra but none of them were ever performed! After his death, it took decades to bring his music to light and have it gain the respect it deserved.

The Leipzig publisher that had initially rejected his Erlkönig, Breitkopf & Härtel initiated a massive Schubert collected edition of 39 volumes in 1884, edited by great artists including Brahms. Schubert’s brother Ferdinand, friends, composers (Schumann, Liszt, Brahms), performers, critics and biographers all played a great role in bringing Schubert’s music to the world after his death. We now have access to a staggering amount of music written in his short lifetime, from his signature Lieder to chamber music to symphonies.

Schubert’s borrowed his motto from Goethe: “I would rather die than be bored.”

Part 2. Franz Schubert’s Music and Most Famous Lieder: From Dark to Light and Everything in Between

Erlkönig

No composer before or since Schubert made such an impact in the genre of art song, known as ‘Lieder’. Although his teacher Salieri (who did not kill Mozart as suggested in the movie Amadeus), encouraged him to use Italian texts, Schubert favoured the great German poets like Goethe or Heine. He also regularly set texts by his friends and contemporaries.

One of his most famous Lied, Erlkönig (Erl-King or Elf-King) with text by Goethe, had a successful first performance. However, the next step of publishing was difficult to achieve. Schubert’s dedicated friends, who often volunteered as his promoters, sent the score to the respected Leipzig publisher Breitkopf & Härtel. The publisher was uninterested and returned the score to the wrong Franz Schubert. Unbelievably, there was another composer with the same name living in Dresden. The other Franz Schubert was insulted that the publisher thought this work was his, saying he’d never write such garbage. The incredible success of the song quickly propelled the correct Franz Schubert to great fame in the genre. Schubert was a notoriously quick writer, usually writing from 6am to 1pm straight through while smoking his pipe. He wrote Erlkönig – one of the most famous art songs in history – in a single afternoon at age 17.

This haunting journey home for father and son was brought to life through an NFB short film.

Click here to watch and listen to Erlkönig.

Pay attention to the terrifying harmony (chords) of the father versus the seductive, beautiful and lighter harmony of the Erl King as he encourages the boy to join him. This juxtaposition creates a horrifying effect.

Ave Maria

Schubert was raised in a very religious household. His school teacher father teaching the subject as part of his duties. In Schubert’s own schooling, religion was his worst subject. He went on to struggle and argue with his father over the topic as an adult. Regarding one of his most famous songs Ave Maria, officially called Ellens Gesang III, Schubert told his parents that it “seems to touch all hearts, and inspired a feeling of devotion. I believe the reason is that I never force myself to be devout, and never compose hymns or prayers of that sort except when the mood takes me; but then it is usually the right and true devotion.” The song is a prayer to the Virgin Mary as part of a collection of seven songs loosely based on Walter Scott’s poem “The Lady of the Lake”.

What you can see from these two contrasting songs is the incredible emotional depth of Schubert’s writing. He was a composer of the early Romantic Era and embraced stories from the human to the supernatural. He was a master storyteller, bringing the human experience to life, from the darkest to the lightest and everything in between.

Lost and Found: Symphony No. 9 in C Major

No orchestra ever performed Schubert’s Symphony No. 9, “The Great” during his lifetime. In 1838, Schubert’s brother Ferdinand showed composer and music critic Robert Schumann the manuscript of Schubert’s Symphony No. 9. This was just a decade after Schubert’s death. Schumann wrote about this work in his music journal and sparked some interest. Schumann sent the music to his friend and colleague Felix Mendelssohn, who performed it with the Gewandhaus Orchestra in Leipzig. This was its first performance. Mendelssohn championed the work as conductor. He programmed this symphony on a trip to London in 1844, however the orchestra refused to play it. Mendelssohn, outraged, pulled his own Overture from the program, inserting Schubert’s instead.

The date of the composition was not always clear. Throughout the 1820’s, Schubert’s health suffered terribly as syphilis took hold. He had somewhat of a reprieve in 1825 when his health was in a good state. At this time, he had the longest holiday of his life at four and a half months. He stayed with a music patron at the picturesque lakeside town of Gmunden surrounded by cliffs, visiting other beautiful Austrian towns such as Gastein.

“The Great”

On this holiday, he announced to his friends that he was writing a grand project – a symphony. This work, known by biographers as the “Gastein” Symphony, was never found. With a little further digging, including looking at the watermarks of the manuscript, they determined that the “Great” C Major Symphony No. 9 (D944) thought to be written in 1828 was actually the so-called lost “Gastein” symphony and written in 1825. Schubert just made some edits in 1828 and added the date. This makes much more sense, as Schubert was in good health in 1825 and able to tackle a massive work.

Interestingly, Beethoven’s influence arises in Schubert’s last movement with a brief quote of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s 9th Symphony. The title of “Great” reflects the majesty of the natural environment he wrote the work in. The symphony may have been read by a conservatory orchestra in Schubert’s lifetime, but it was only performed after other romantic era composers discovered and championed it a decade after Schubert’s death.

In the late 1950s, conductor René Leibowitz recorded this symphony without traditional performance techniques of the day that would have altered the piece. Instead, Leibowitz created a recording loyal to the original score. Watch the video below to hear the third and fourth movement of this version of Schubert’s “Great” Symphony!

Celebrate Schubert at our Composer Festival

Learn all about Franz Schubert throughout our Schubert Composer Festival events from April 1 to April 15! The first week of events includes a free Community Recital, a Happy Hour at Shawn & Ed’s Brewing Co. and music appreciation talks in Hamilton and Burlington.

Then, we have our Schubert Talk & Tea, a music appreciation talk around all the works the HPO performs at our concert the following day. The festival concludes with our mainstage concert, An Evening with Schubert, where we will hear Ave Maria and Schubert’s Symphony No. 9. Sarah Ioannides joins us as guest conductor, and London Ontario-born Alexandra Smither is our guest soprano.

Talk & Tea: Schubert

Friday, April 14 at 11am

FirstOntario Concert Hall (Stage Door)

An Evening with Schubert

Saturday, April 15 at 7:30

FirstOntario Concert Hall