Nancy Nelson, an oboe player and long-time member of the HPO, recently spoke with Composer-in-Residence Abigail Richardson-Schulte about her career as an oboe and english horn player, the joys of working with Music Director Gemma New and the intricacies of reed making.

Abigail Richardson-Schulte: Hi Nancy! It’s great to be in touch with you. How have you been doing?

Nancy Nelson: Well, I think like everybody else I’ve been on an emotional rollercoaster. Some days I just wake up and wonder what I should do today. I have been keeping busy practicing, making reeds, experimenting with new reed gouges and different kinds of cane. I jog, swim, garden and have cleaned every closet. I’ve also been working on church music although it will be a while before church returns and there certainly won’t be singing.

My students didn’t want to stop lessons when this hit so I have been teaching oboe and piano through FaceTime. If my oboe students need reeds, I put a couple of containers in the mailbox for them to pick up.

ARS: Now, you’ve been with the HPO for a long time, right?

NN: I started playing as an extra in my third year of studying music education at McMaster. I auditioned for the position a few months after graduating and won it.

ARS: That’s very fast, wow. I imagine the organization is a lot different from when you joined. Has anything stayed the same?

NN: The thing that stays the same is the rehearsal and performance of great music. That work of a musician doesn’t change. The conductors and conducting styles have changed. I played with conductors Boris Brott, Mario Bernardi, Victor Feldbrill and now years later, with Gemma New. I don’t know if I have ever felt so content or appreciated. She is all about the music and she doesn’t have favourites. She is there to do the utmost to make our performing as magnificent as possible but she’s also especially human.

The management, you, all the people, make it a wonderful place to be. I started my orchestral career at the end of the old generation that often thought they needed to command respect through fear.

ARS: That old style of conducting isn’t tolerated like it once was. Was becoming a professional oboist always an obvious path for you?

NN: Not at all. I was good at math and geography and thought I might become a teacher. I applied to McMaster in both music and geography but chose to pursue music education. During my third year of university, I was hired as an extra with the HPO. We played Mahler’s 4th Symphony and I was hooked.

I’ve had an amazing career in orchestra but also playing shows at Shaw and Stratford [Festivals]. I also teach at McMaster. I can’t say there is anything I still need to do, except that through circumstances I never ended up playing Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat. I think a lot of my success is that I have been in the right place at the right time. People hired me as a sub and they were happy with what I did, so they hired me back.

ARS: You have a new colleague in the orchestra. The HPO recently hired a new principal oboe, Aleh Remezau.

NN: My music teacher in high school said playing music is like a marriage: you have to give and take and you’re not always right. I’m really pleased that Aleh and I work so well together. Aleh is terrific – the whole package. He plays well, works very hard and is a wonderful human. He also accepts that the people around him have played for longer and he works very collaboratively.

ARS: Sadly, former HPO Music Director Victor Feldbrill died last month. I’ve seen you quoted several times about Feldbrill, and I know he had the HPO commission an english horn concerto for you (Divertimento No. 11) from legendary Canadian composer John Weinzweig. Can you share some memories about Victor Feldbrill?

NN: All I can ever remember about Victor was when he got on that podium, there was an aura around him. He demanded 100% attention but he never asked for it. Everybody appreciated working with Victor. He was knowledgeable and on the ball. Off the podium, he was another human. He loved everybody.

ARS: That’s nice to hear. He was such an advocate for Canadian composers and their music. I look forward to listening to the Weinzweig piece you premiered! Speaking of english horn, I always think of it as the slightly darker cousin to the oboe. Is there much of a difference in playing the oboe and the english horn and are all oboists expected to play it?

NN: All oboists are expected to play it although there are many that don’t actually own one. They borrow an instrument if they need it. I do not play the english horn and the oboe the same at all. To be a specialist on the english horn, you have to think of it as an entirely different personality and entity. It has such a different timbre and the music written for it is very different as well. You have to appreciate what it is capable of: the dark, the rich, the resonant. You can tell a specialist when you hear them play. I think the personality of the person needs to be a match as well. I classify myself as an english horn specialist.

Learn more about the differences and similarities between the English horn and the oboe in this video from the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra!

ARS: Let’s talk about reeds. First of all, the oboe is classified as a “double reed,” like the bassoon. What does that mean?

NN: In the easiest of terms, it means that we use a reed which is actually two reeds tied together so that they can vibrate with each other.

ARS: I know professional oboe players spend a long time making their own reeds. Can you give us a rundown of how you make a reed, how long it takes, and how long it lasts?

NN: First of all, factory-bought double reeds don’t cut it so professionals have to make our own. The best cane comes from areas of France but every piece has a different quality so there is always work involved with trying to make them all play as much the same as possible. Even if it is the same piece of tube cane, you will never get exactly the same results twice, like a snowflake. We do our best to constantly aim for the same results and make the “perfect” reed.

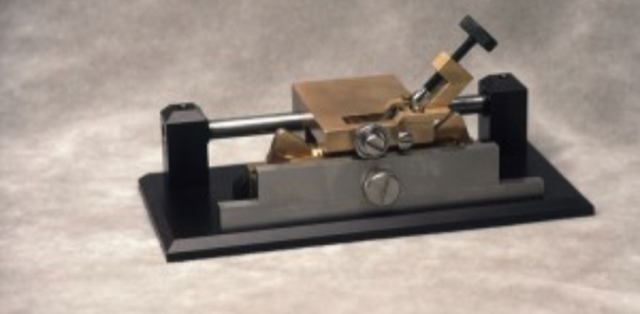

First, you split your cane lengthwise into three pieces with an arrowhead-shaped splitter and then place it on a special oboe cane planer so it is not too thick and wide to put into the gouge machine. It is then set it into the bed on the machine and gouged with a semi-circular blade to get about a 0.6mm middle which gets thinner towards the sides (the numbers vary ever so slightly from player to player).

I personally then soak the cane in water for 20 minutes, fold it in half, put on a shaper tip, and scrape off the sides to form the characteristic shape of the oboe reed cane, and thin the bases so that it doesn’t crack when tying it onto the staple with special oboe reed thread. That process yields a blank which will then take another 5-15 minutes to actually create a finished reed.

We use special reed knives to carefully scrape the wood off the blanks. 98% of my reeds turn out, which is a high yield and lucky for me! Making one reed might take an hour or two from start to finish, but generally, gouging is done at one time and the actual reed making at another time which for me is more efficient.

After the reed is made, it needs to dry out which changes the cane wood. Then it will be reworked again, possibly over a number of days before I feel confidant to play it in concerts. A reed will typically last a week of concert playing and perhaps a little more just for practice. Then again, certain pieces will kill a reed with one performance. Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice is one of those.

My theory is that reeds need a few seconds of break to recoup. If they don’t have that throughout the piece, I feel they wear out faster. This is half of our battle as oboists.

ARS: Once they are made, are reeds temperamental?

NN: A lot of other people have more temperamental reeds. They complain about the heat, cold, humidity, dryness. We all have our reasons to complain but I try not to complain about my reeds because no one can help me with it. Each oboe player’s reed is different, almost like a signature.

ARS: Oh, that’s why musicians are so concerned about the temperature of the hall!

NN: Yes, not only because of the reeds but also because instruments can crack when we blow warm air into a cold instrument. For the most part, cracks are not covered by insurance.

ARS: I finally understand why this is an issue. Now, making reeds sounds like such a specialized skill. Is this part of oboe lessons?

NN: Yes, oboe reed making is absolutely part of learning to play the oboe. I got a scholarship to attend summer music camps. While other students were having “sessionals” (focused practices for just one type of instrument), we were having reed making sessions.

ARS: Can you tell me about your oboe and what it is made out of?

NN: I have two Lorée oboes. One of them is a bigger oboe than the other. The smaller one works very well for Bach, Mozart, and Haydn with more of a covered, less conspicuous sound. My larger oboe is great for romantic works like Mahler. I have a Lorée english horn, and I also have a plastic Fox professional model for outdoor use. Student models are plastic. My oboes are made out of grenadilla wood but apparently the supply is running out. They may be starting to use cocobolo wood. I’m glad I’m at this end of my career.

ARS: I recently discovered an article about “the oboe doctor of Parkdale” which mentions you and your oboe.

NN: Ha, how did you find that article? Gary is retired now and I have had to find other oboe doctors. His wife is a violinist and occasionally plays with the HPO, by the way. Gary knew my oboe, my playing, and was an oboist himself. He knew I have a light touch and how to balance the oboe accordingly.

Oboes are set up for factory specs but really need to be adjusted to the individual player. The instrument is a bit like a teeter-totter with one key having multiple functions. For example, one key might close but another attached to it might not if a screw is too tight. Also, if your instrument cracks, you need to get it fixed immediately. There are some of us that can do repairs. I can do a fair amount of repairs myself.

ARS: I was really surprised to learn that you are also a church organist! Have you always been an organist while also playing oboe in the HPO? Where do you play?

NN: I’ve always been a pianist. I got my grade 10 piano before I went to university but I didn’t play the organ. That sort of happened by accident. People knew I was a keyboard player and asked me to sub for them at a couple of Watertown churches on the organ. In 2003, the Music Director position came up at Christ Church Flamborough and I’ve been there ever since. I have a steadfast 9 member choir, half of whom read music.

ARS: Well thank you for speaking with me, Nancy. I have a new appreciation for reed making, temperature control and the english horn. I wish you all the best and hope to hear you playing your oboes, english horn and organ soon!