By: Abigail Richardson-Schulte

HPO Composer-in-Residence

As a kid, I loved the Choose Your Own Adventure books. I would read them backward and forwards to find all imaginable endings. For Rimsky’s Korsakov’s Scheherazade, you can choose your own adventure. Let me explain:

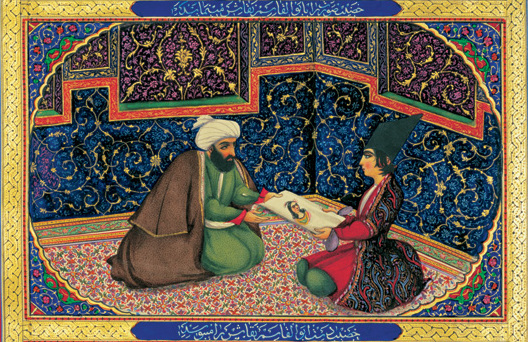

One Thousand and One Nights is a varied collection of ancient stories mainly of Arabic, Indian and Persian origin. Aladdin, Ali Baba and Sinbad are amongst the most famous of the collection. In 1888, Rimsky-Korsakov decided to write his own symphonic version of the tale of Scheherazade which comes from the One Thousand and One Nights collection. Rimsky-Korsakov initially wrote a sort of story guide in his score but omitted this in the second publication of the work:

“The Sultan Shahriar, convinced of the duplicity and infidelity of all women, vowed to slay each of his wives after the first night. The Sultana Scheherazade, however, saved her life by the expedient of recounting to the Sultan a succession of tales over a period of one thousand one nights. Overcome by curiosity, the monarch postponed the execution of his wife from day to day, and ended by renouncing his sanguinary resolution altogether.”

Rimsky-Korsakov was frustrated by listeners trying to relate every musical element to an element of the story. Also, as was common in the day, programmatic symphonic works were less likely to be taken seriously and so Rimsky-Korsakov presented his work as inspired by these stories rather than a direct telling of them.

“In composing Scheherazade I meant these hints to direct but slightly the hearer’s fancy on the path which my own fancy had traveled, and to leave more minute and particular conceptions to the will and mood of each. All I had desired was that the hearer, if he liked my piece as symphonic music, should carry away the impression that it is beyond doubt an Oriental narrative of some numerous and varied fairytale wonders and not merely four pieces played one after the other and composed on the basis of themes common to all the four movements.”

Each of the four movements were given a descriptive title:

I. The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship

II. The Story of the Kalendar Prince

III. The Young Prince and the Young Princess

IV. The Festival of Baghdad—The Sea—The Ship Goes to Pieces Against a Rock Surmounted by a Bronze Warrior—Fest in Baghdad

Rimsky-Korsakov cautioned against trying to find themes for each story although he did identify Scheherazade’s theme very close to the beginning of the work. It is a theme played by the solo violin and accompanied by the harp. This captivating theme draws us in as any great storyteller would. The theme returns throughout the work as Scheherazade weaves her storytelling web. Many analysts also point to the opening low brass theme belonging to the character of the Sultan although Rimsky-Korsakov did not confirm this himself. To hear and understand these musical characters, I encourage you to listen to the first minute or so of Scheherazade. You’ll hear first this bold, evil-sounding Sultan’s theme followed by a short transition of woodwind chords which give way to the stunning Scheherezade theme in the violin. From here, she takes us on different journeys specific to each movement but brings along the collected themes from previous movements, transforming them to the current situation.

As a musical storyteller, it is difficult to keep a story perfectly on track without a singer or narrator. Rimsky-Korsakov solves this problem by suggesting only the situation but nothing more. Listeners know the setting and characters through the movement titles as well as the voice of Scheherezade. From there, we are encouraged to imagine the scene unfolding as it is told to us. This is a way for us, the listeners, to more actively use our imaginations: to wonder and imagine the great adventures of these ancient characters. This is a true Choose Your Own Adventure musical experience.